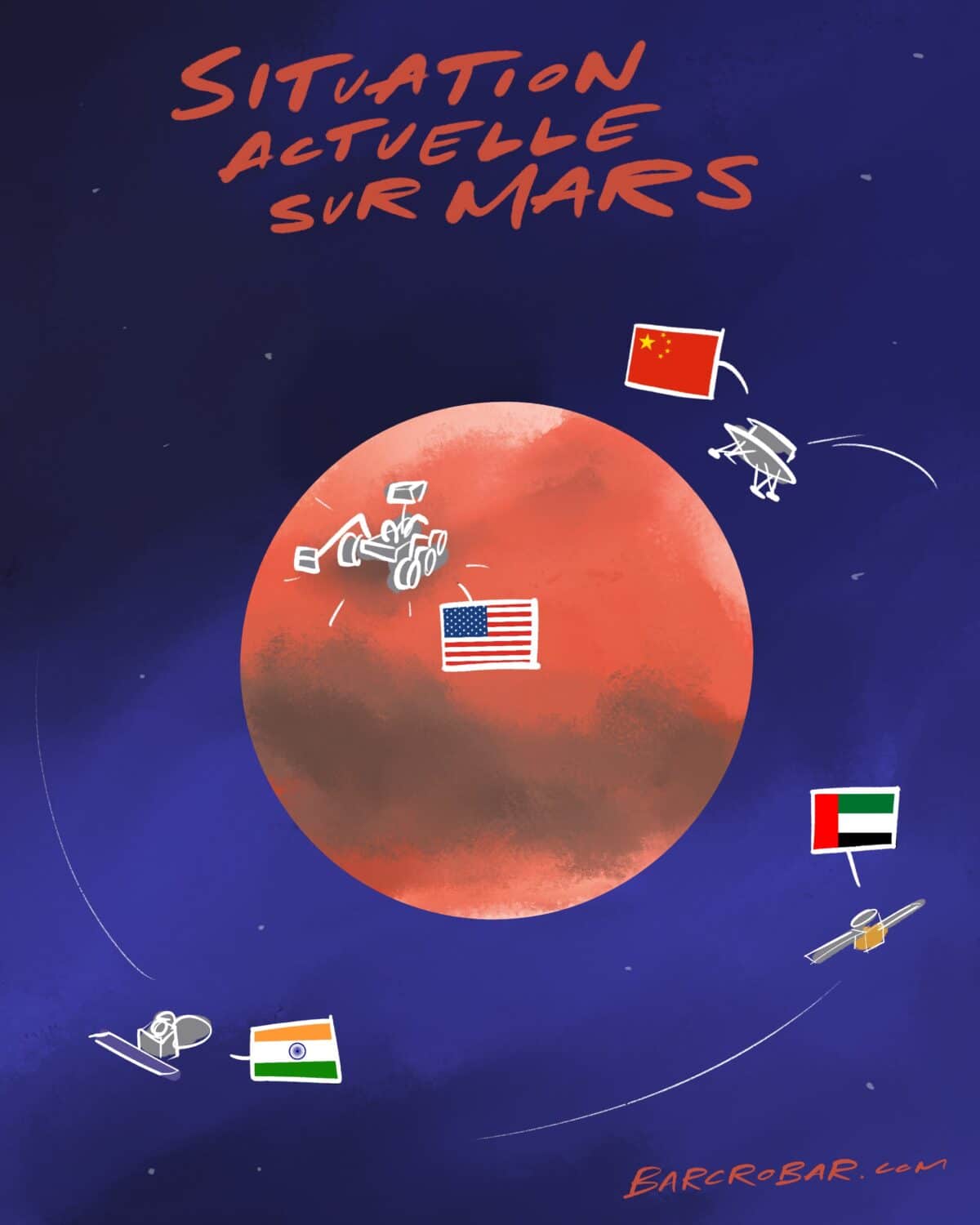

All eyes on the stars. NASA's Perseverance mission landed on the Red Planet on Thursday 18 February. It is the third mission to arrive on Mars in a week, along with those from the United Arab Emirates and China. The Tianwen-1 probe arrived in the planet's orbit on 10 February. In the spring, it is due to land a remote-controlled wheeled robot on the Martian surface. This mission will enable Beijing to pursue its ambitions for space conquest, which began under Mao sixty years ago. The country "dreams of space", in the words of Chinese President Xi Jinping. For The Conversation, Steffi Paladini, from the University of Birmingham, deciphers these dreams.

Given its achievements over the last decade, it's only logical that China should be looking to win the new space race. Not only has it been the only country to send a probe to the Moon in the last forty years or so - and the first in history to successfully land on its far side - but it has also planted a flag on lunar soil and brought samples back to Earth.

However, the space race, in which several nations and private companies are taking part, is far from over. China is now turning its attention to Mars with its Tianwen-1 mission, which arrived in Martian orbit on 10 February. This successful insertion into orbit - the rover will not land until May - marks a crucial new stage in more ways than one.

Even though Mars is relatively close to Earth, it's a tough target to hit. Nothing demonstrates this better than the figures. Out of 49 missions up to December 2020, only around 20 have been successful. Not all of these failures were the result of novices or first attempts. In 2016, the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli Mars Explorer crashed on the surface of the Red Planet. In addition, persistent technical problems have forced ESA and its Russian partner Roscosmos to postpone its next mission, ExoMars, until 2022.

China is not the only country to get close to Mars. On 9 February, a probe from the United Arab Emirates, Hope, successfully completed the same insertion manoeuvre. It is not a direct competitor of the Chinese mission (the probe will only orbit the planet to study the Martian weather), but NASA's Perseverance rover, which arrived a week later, is undoubtedly.

One factor makes the stakes even higher for Beijing: one of the few countries to have successfully performed the famous in-orbit insertion manoeuvre is India, China's direct competitor not only in space but also on Earth.

India's Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), aka Mangalyaan, reached Mars in 2014 - it was the first to achieve this feat on its inaugural mission. This is one of the reasons why the success of Tianwen-1 is so important for China's status as an emerging space power: it's a way of reasserting its space dominance over its neighbour. Unlike India, this is not the first time China has attempted a mission to Mars (the previous one, Yinghuo-1, in 2011, failed on launch). This time, however, the chances of success look much better.

The space age 2.0

Different countries have different space development models. The new space race is therefore partly a competition for the best approach. This reflects the specific character of the Space Age 2.0, which, compared with the first, seems to be more diversified and where non-American players, both public and private, occupy an important place, particularly Asian players. If China is leading the pack, so too is its vision.

But there are more important issues at stake. The development of China's space sector is still largely government-funded and military-led. According to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a US congressional committee, China sees space as a "tool for geopolitical and diplomatic competition". Clearly, with cyberspace, the cosmos has become a fundamental new battleground, where the United States is the main - but not the only - adversary. This means that commercial considerations are taking a back seat for many countries, even if they are becoming increasingly important as a general rule.

China has already adopted five-year plans for its space activities. The most recent ended in 2020 with more than 140 launches. Other missions are planned, including a new orbital space station, the recovery of Mars samples and a mission to explore Jupiter.

While the resources committed by the country remain largely unknown (we only know what is included in the five-year plans), US estimates for 2017 are $11 billion, putting China second only to the US itself - NASA's budget for the same year was around $20 billion.

India has adopted a different approach, where civil and commercial interests predominate. Following NASA's model of transparency, the country publishes reports on the activities and annual expenditure (around US$1 billion a year) of its space agency, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

Different in ambition, scope and investment, India's space programme has achieved remarkable successes, such as the commercialisation of affordable launch services for countries wishing to send their own satellites into orbit. In 2017, India made history with the most satellites - 104 - ever launched by a rocket on a single mission to date (all but three were foreign-built and foreign-owned). This record was broken by SpaceX in January 2021, with 143 satellites. Even more impressive is the relatively low cost of India's Mars mission, 74 million US dollars - around ten times cheaper than NASA's Maven mission. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said the entire mission cost less than the Hollywood film Gravity.

For geopolitical reasons, this could soon change. The Indian government has published its 2019-2020 annual report, which shows growing military involvement in the space sector. And further missions to the Moon and Venus are planned by India's ISRO, as if to further motivate the Chinese to make Tianwen-1 a resounding success. The space race 2.0 is gaining momentum...![]()

Steffi Paladini, Reader in Economics & Global Security, Birmingham City University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.